When we do time series analysis, we are usually interested either in

- uncovering causal relationships (Does XtXt influence Yt+1Yt+1?) or

- in getting the most accurate forecast possible.

Especially in the second case it can be beneficial to transform our historical data to make it easier to extract a signal.

A very common transformation is to take logs. By taking logs we can often stabilize the variance of our series and hopefully make a non-stationary series stationary. Furthermore, taking logs has a nice interpretation as approximate percentage changes. However, taking logs requires that our data is strictly positive, which although true for many practical applications, might not hold in our particular situation.

A more general class of transformations are power transformations such as the Box Cox transformation that includes logs as a special case:

y(λ)i={y(λ)i−1λ if λ≠0ln(yi) if λ=0y(λ)i={y(λ)i−1λ if λ≠0ln(yi) if λ=0

The Box Cox transformation was designed to help make data more ‘normally’ distributed and thus help stabilize its variance. Forecasting the transformed series can be substantially simpler.

Note that when we use the Box Cox transformation and forecast on the transformed scale we cannot simple reverse the transformation to get the mean forecast on the original scale since for our convex backtransformation function ff Jensen’s inequality tells us that:

f(E[X])≤E[f(X)] If the data on the transformed scale is symmetric, we will get the forecast median on the original scale instead of the mean, since medians are not affected by monotonic transformations.

So if we simply backtransform our mean forecast without bias adjustment, our forecast will be systematically too low. To correct the bias we can use a Taylor expansion of our backtransformation function f:

E[f(X)]=E[f(μX+(X−μX))]≈E[f(μX)+f′(μX)(X−μX)+12f″(μX)(X−μX)2]=f(μX)+f″(μX)2σ2X⏟bias adjustment

Fortunately, R’s forecast package allows us to easily apply this bias correction without having to calculate it manually.

No time series example in R is complete without taking a look at the AirPassengers dataset:)

We will start by visually comparing the original and the Box Cox tranformed time series. Then I will fit SARIMA and ETS models to the original and the transformed series and check if the Box Cox transformation helps to improve forecasting accuracy.

Does the Box Cox transformation help improve forecasts?

I will rely on the following libraries:

library(data.table)

library(ggplot2)

library(grid)

library(gridExtra)

library(forecast)##

## Attache Paket: 'forecast'## The following object is masked from 'package:ggplot2':

##

## autolayerlibrary(magrittr)

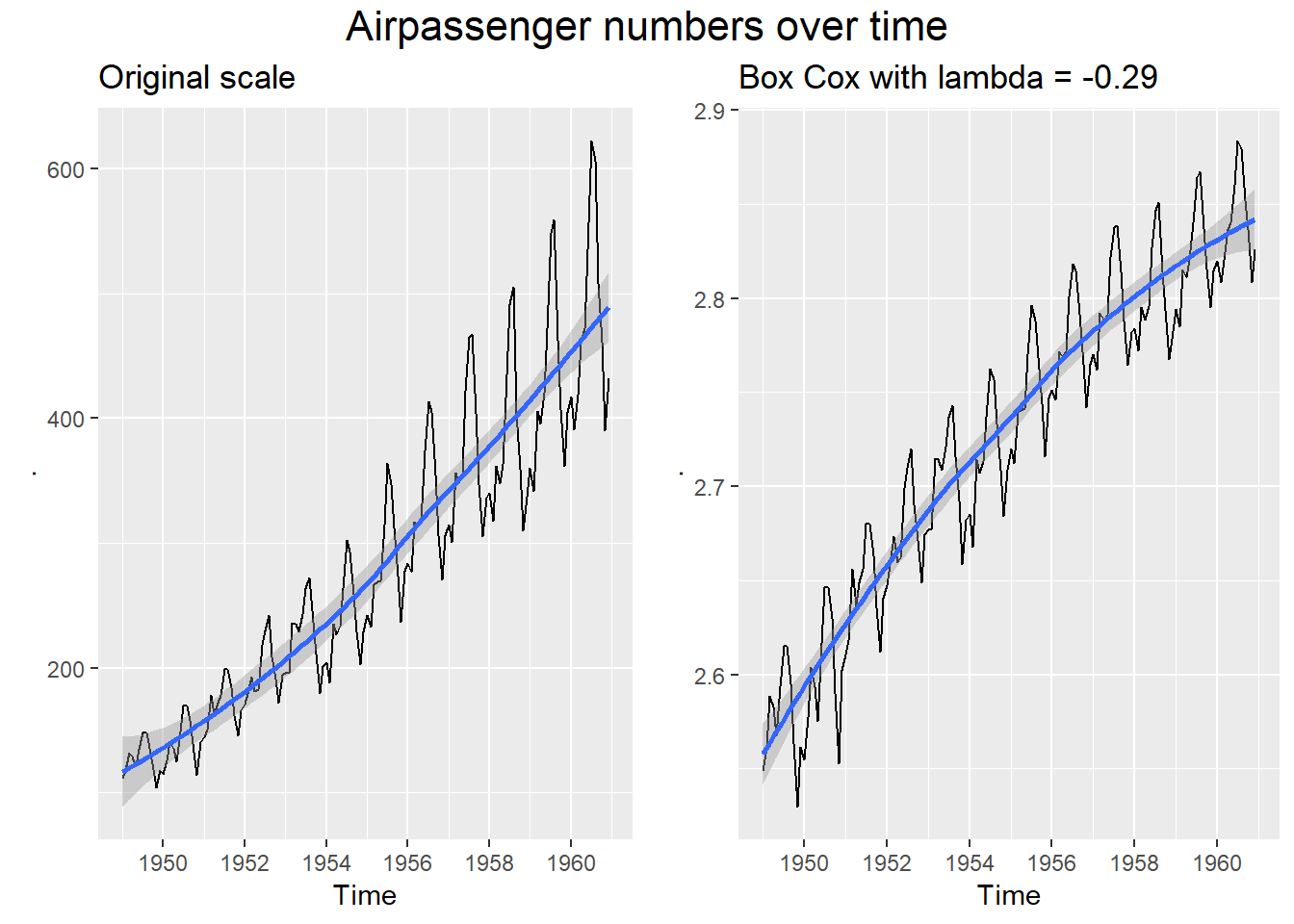

library(future)The AirPassengers dataset shows the growth in passenger numbers over time on a monthly basis. Let’s create a quick plot comparing the original with the Box Cox transformed dataset. We choose lambda automatically based on minimizing the coefficient of variation (σ/μ) of the subseries of the Airpassengers series (see Hyndman).

## Original dataset

air_orig = AirPassengers %>%

autoplot() +

geom_smooth() +

ggtitle("Original scale")

## Transformed dataset

AirPassengersBoxCox = BoxCox(AirPassengers, lambda = "auto")

air_box = AirPassengersBoxCox %>%

autoplot() +

geom_smooth() +

ggtitle(paste0("Box Cox with lambda = ",

round(attributes(AirPassengersBoxCox)$lambda,2))

)

## Comparision

grid.arrange(air_orig, air_box, ncol = 2,

top = textGrob("Airpassenger numbers over time",

gp = gpar(fontsize = 16))

)## `geom_smooth()` using method = 'loess' and formula 'y ~ x'

## `geom_smooth()` using method = 'loess' and formula 'y ~ x'

We can clealy see that the original series has a trend and increasing volatility, so it is not stationary. Applying a Box Cox transformation helped us get near constant volatility over the entire time period. We can also see the seasonal pattern of both series.

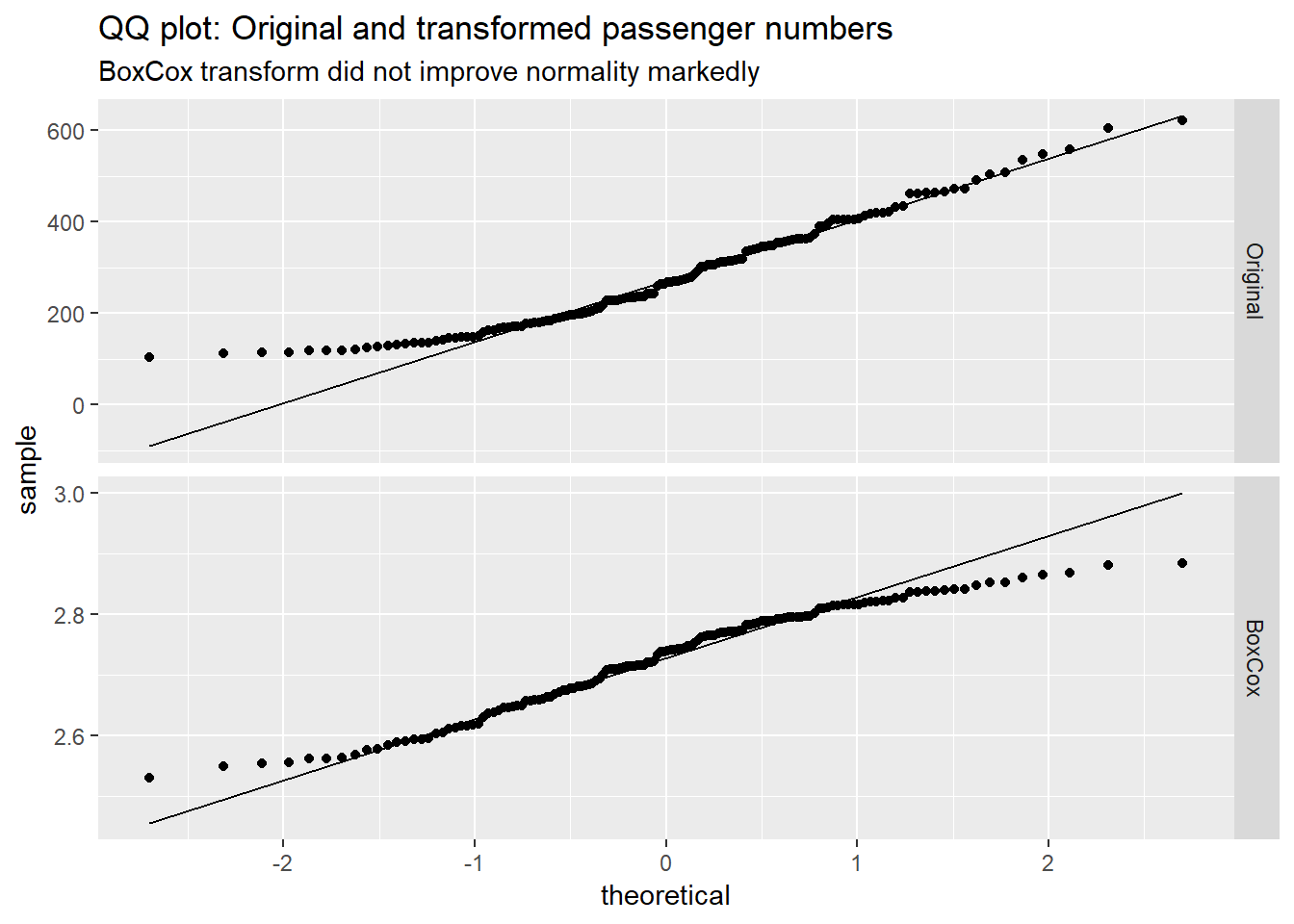

Let’s quickly look at a histogram to check if the transformation actually helped to make our data more normal:

df_hist = data.frame(passengers = as.double(AirPassengers), type = "Original")

df_hist = rbind(df_hist, data.frame(passengers = as.double(AirPassengersBoxCox), type = "BoxCox"))

ggplot(df_hist, aes(sample = passengers)) +

geom_qq() +

geom_qq_line() +

facet_grid(type ~ ., scales = "free_y") +

ggtitle("QQ plot: Original and transformed passenger numbers",

"BoxCox transform did not improve normality markedly") So, while the Box Cox transformation helped to stablize variance, it did not really help a lot with improving normality.

So, while the Box Cox transformation helped to stablize variance, it did not really help a lot with improving normality.

As already mentioned, we are now going to fit two types of models to the series:

- exponential smoothing (ETS) and

- SARIMA models

with and without a Box Cox transformation and see how they compare.

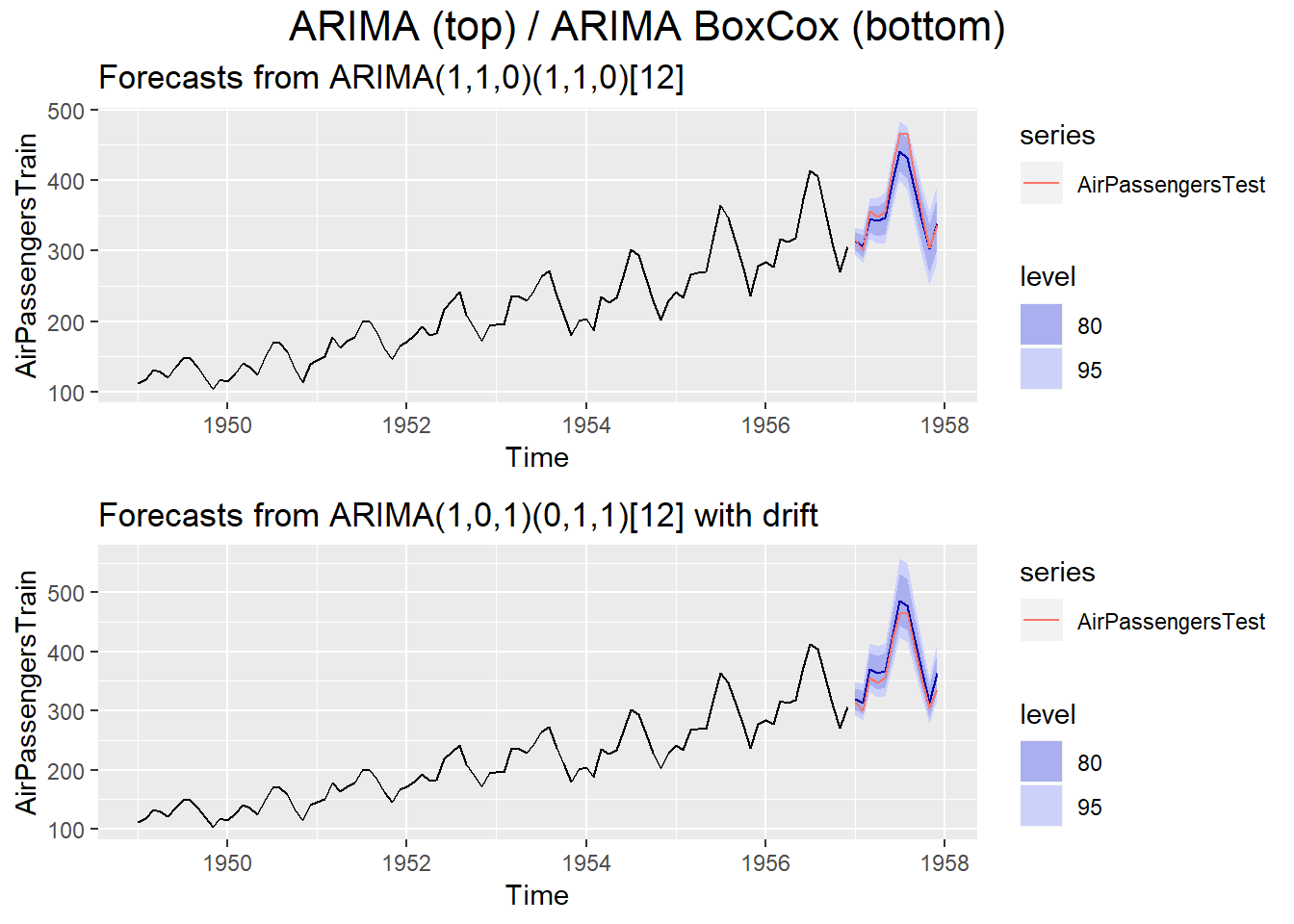

We will start off by training models on all years including 1956 and predicting the following year, i.e. 12 periods ahead to get a feeling for the different models:

AirPassengersTrain = window(AirPassengers, start = c(1949, 1), end = c(1956, 12))

AirPassengersTest = window(AirPassengers, start = c(1957, 1), end = c(1957, 12))Let’s train the models and create some plots:

plot_arima = forecast(auto.arima(AirPassengersTrain), h = 12) %>%

autoplot() +

autolayer(AirPassengersTest)

plot_arima_box = forecast(auto.arima(AirPassengersTrain, lambda = "auto", biasadj = T), h = 12) %>%

autoplot() +

autolayer(AirPassengersTest)

grid.arrange(plot_arima, plot_arima_box, ncol = 1,

top = textGrob("ARIMA (top) / ARIMA BoxCox (bottom)",

gp = gpar(fontsize = 16))) The models picked up on the yearly seasonality in both cases and overall both models perform similarly.

The models picked up on the yearly seasonality in both cases and overall both models perform similarly.

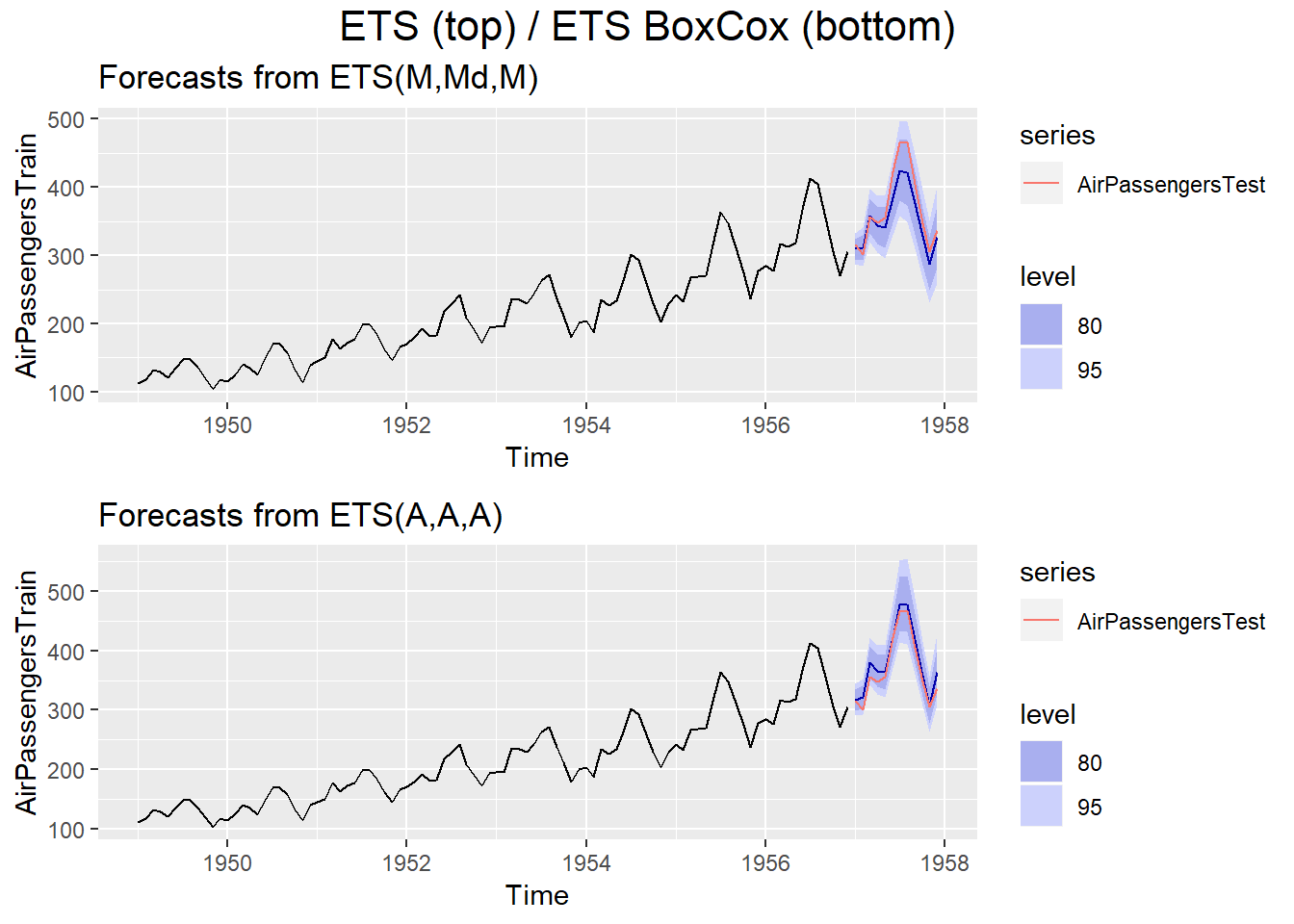

plot_ets = forecast(ets(AirPassengersTrain, allow.multiplicative.trend = T),

h = 12) %>%

autoplot() +

autolayer(AirPassengersTest)

plot_ets_box = forecast(ets(AirPassengersTrain,

allow.multiplicative.trend = T,

lambda = "auto", biasadj = T),

h = 12) %>%

autoplot() +

autolayer(AirPassengersTest)

grid.arrange(plot_ets, plot_ets_box, ncol = 1,

top = textGrob("ETS (top) / ETS BoxCox (bottom)",

gp = gpar(fontsize = 16)))

We can see that the vanilla ETS model is performing clearly worse than the ETS-BoxCox version. This suggests that whether a Box Cox transformation helps, depends in large parts on the model in question.

To get a more accurate picture of model performance with(out) Box Cox transformation, we will run a time series cross-validation:

Before we start, we define a few helper functions:

rmse_horizon = function(errors, start = c(1950, 1)) {

## removing the first year because of insufficient data

errors = window(errors, start = start)

rmse = function(x) sqrt(mean(x^2, na.rm = T))

apply(errors, MARGIN = 2, FUN = rmse)

}Since the computations take quite some time we will run them async so the current R session is not blocked. We use a ‘multisession’ execution plan, i.e. each core gets to execute one R session in the background. As soon as all cores are busy, evaluation of other futures is blocked.

plan(multisession, workers = 2)Let’s get started:

## setup

data = AirPassengers

h = 12

##ets

forecastfunction = function(x, h) forecast(ets(x, allow.multiplicative.trend = T), h = h)

rmse_ets %<-% {

tsCV(data, forecastfunction = forecastfunction, h = h) %>%

rmse_horizon()

}

##ets box

forecastfunction = function(x, h) forecast(ets(x, allow.multiplicative.trend = T,

lambda = "auto", biasadj = T), h = h)

rmse_ets_box %<-% {

tsCV(data, forecastfunction = forecastfunction, h = h) %>%

rmse_horizon()

}

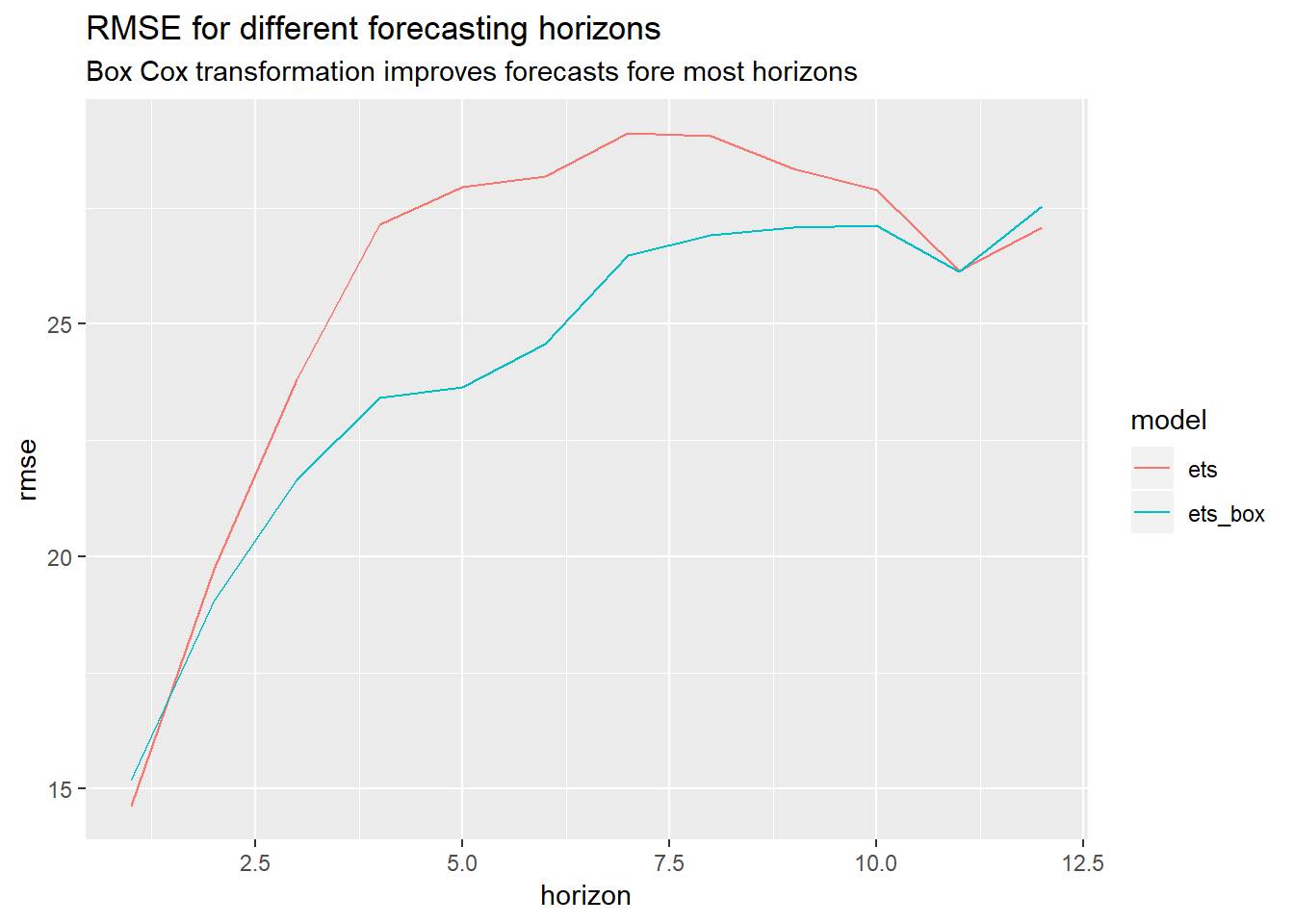

##Comparison chart:

rmse_ets_compare = data.frame(rbind(rmse_ets, rmse_ets_box))

rmse_ets_compare %>%

cbind(model = c("ets", "ets_box"), .) %>%

tidyr::gather(key = "h", value = "rmse", 2:13) %>%

dplyr::mutate(horizon = rep(1:12, each = 2)) %>%

ggplot(., aes(x = horizon, y = rmse, color = model)) +

geom_line() +

ggtitle("RMSE for different forecasting horizons",

"Box Cox transformation improves forecasts fore most horizons")

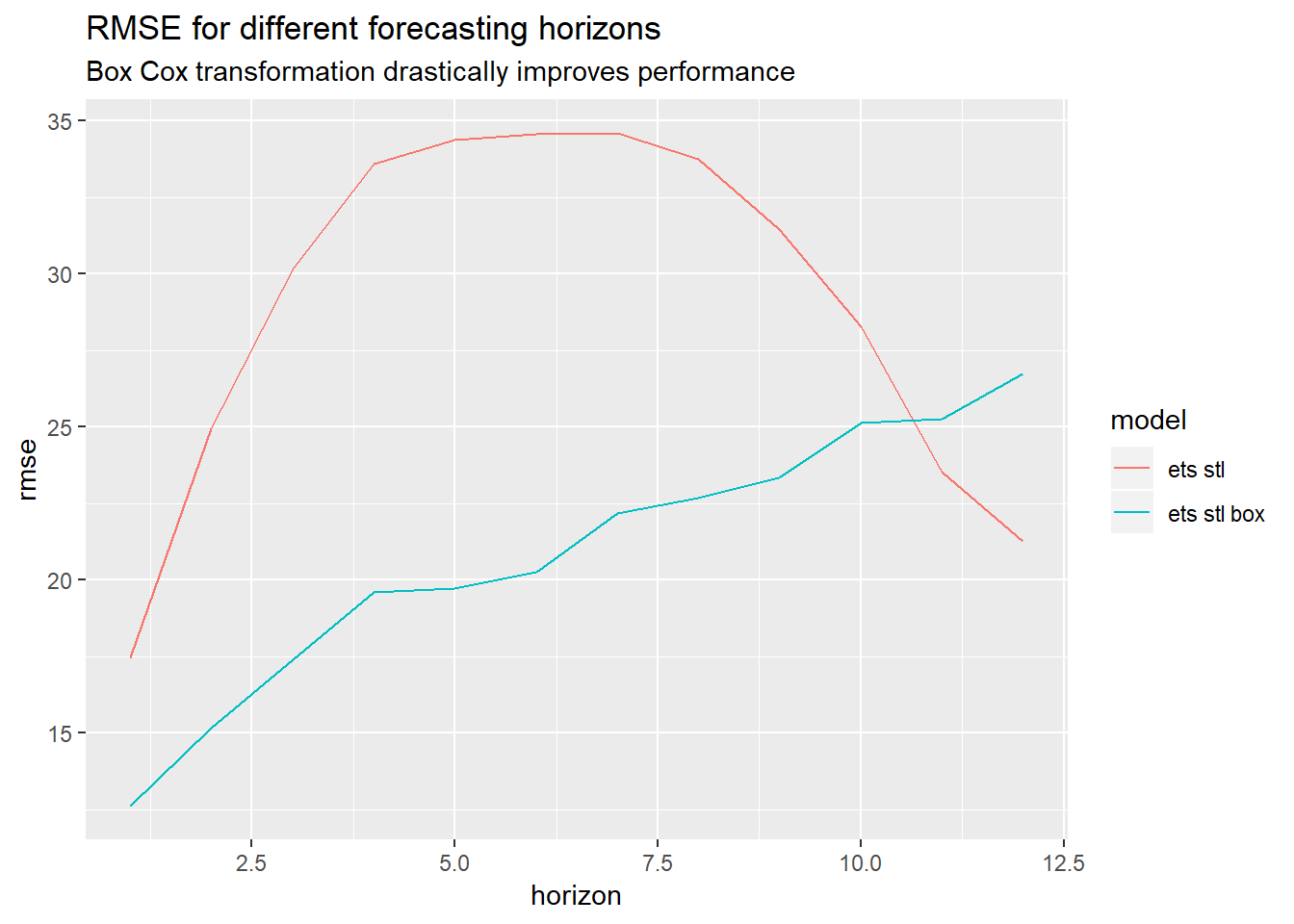

As we can see in the chart above, applying a Box Cox transformation helped to improve performance for most forecasting horizons as we already expected based on the chart in the beginning.

Now let’s try again with SARIMA models:

## setup

data = AirPassengers

h = 12

##arima

forecastfunction = function(x, h) forecast(auto.arima(x), h = h)

rmse_arima %<-% {

tsCV(data, forecastfunction = forecastfunction, h = h) %>%

rmse_horizon()

}

##arima box

forecastfunction = function(x, h) forecast(auto.arima(x, lambda = "auto", biasadj = T), h = h)

rmse_arima_box %<-% {

tsCV(data, forecastfunction = forecastfunction, h = h) %>%

rmse_horizon()

}

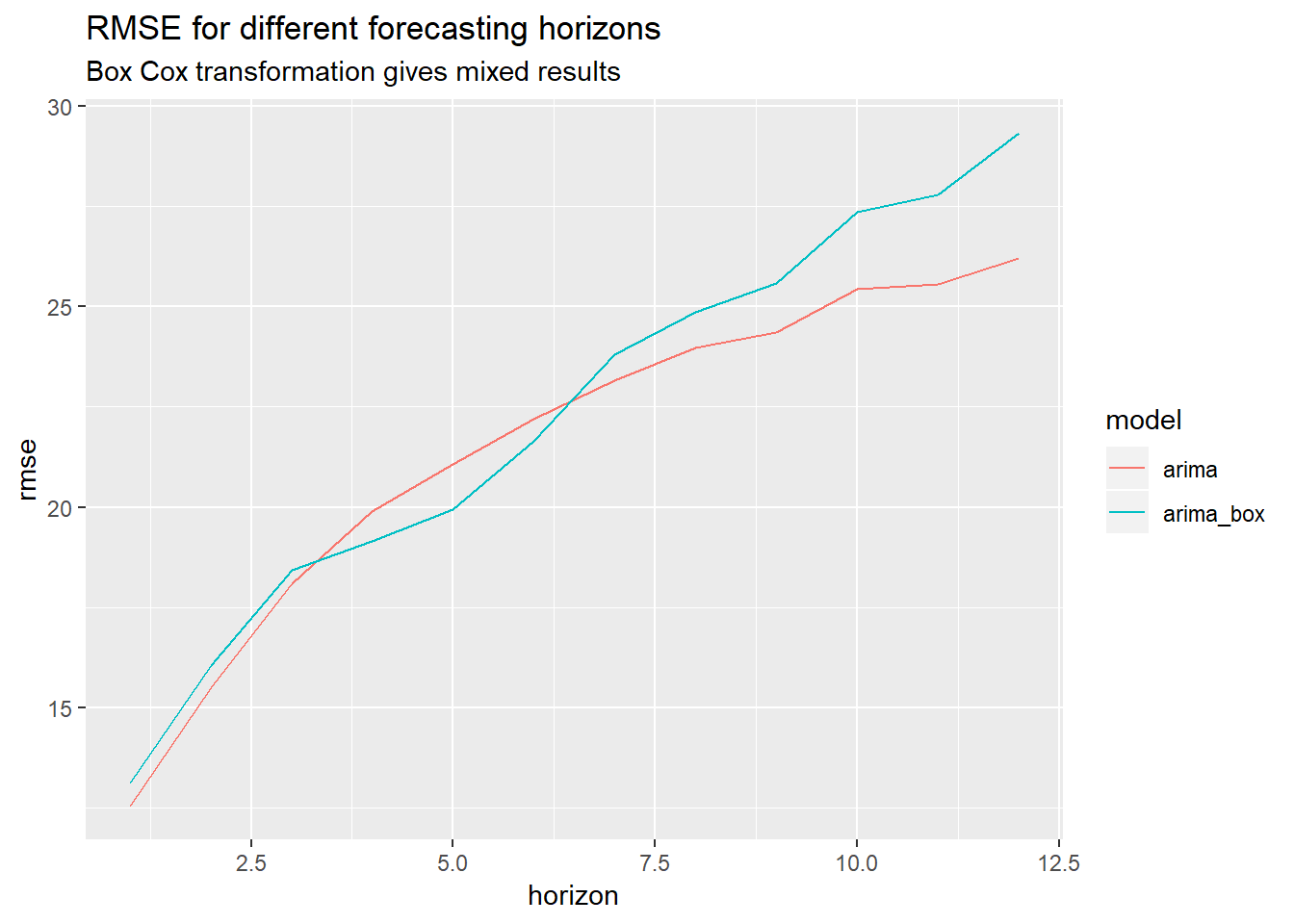

##Comparison chart:

rmse_arima_compare = data.frame(rbind(rmse_arima, rmse_arima_box))

rmse_arima_compare %>%

cbind(model = c("arima", "arima_box"), .) %>%

tidyr::gather(key = "h", value = "rmse", 2:13) %>%

dplyr::mutate(horizon = rep(1:12, each = 2)) %>%

ggplot(., aes(x = horizon, y = rmse, color = model)) +

geom_line() +

ggtitle("RMSE for different forecasting horizons",

"Box Cox transformation gives mixed results")

In the SARIMA case, the result is not really clear cut: the Box Cox transformation helps slightly for some time horizons, while making it worse for others. Since there is no clear winner, we stick to the simpler plain-vanilla SARIMA model. Again, this confirms what we saw during our initial exploration in the beginning where ARIMA with(out) Box Cox performed more or less the same.

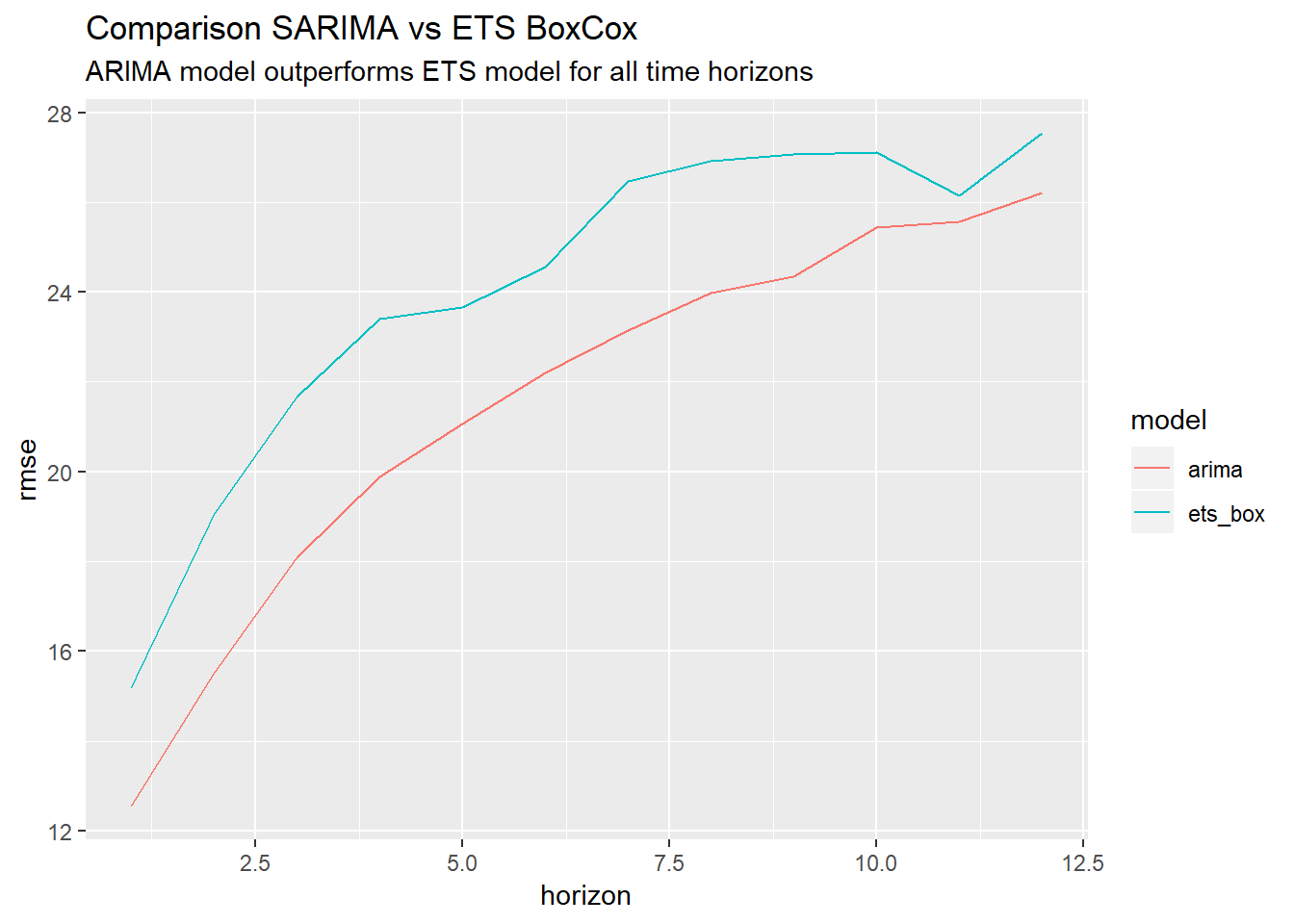

How does the SARIMA model compare with the Box Cox ETS model?

So in this case, a plain vanilla ARIMA model actually works best.

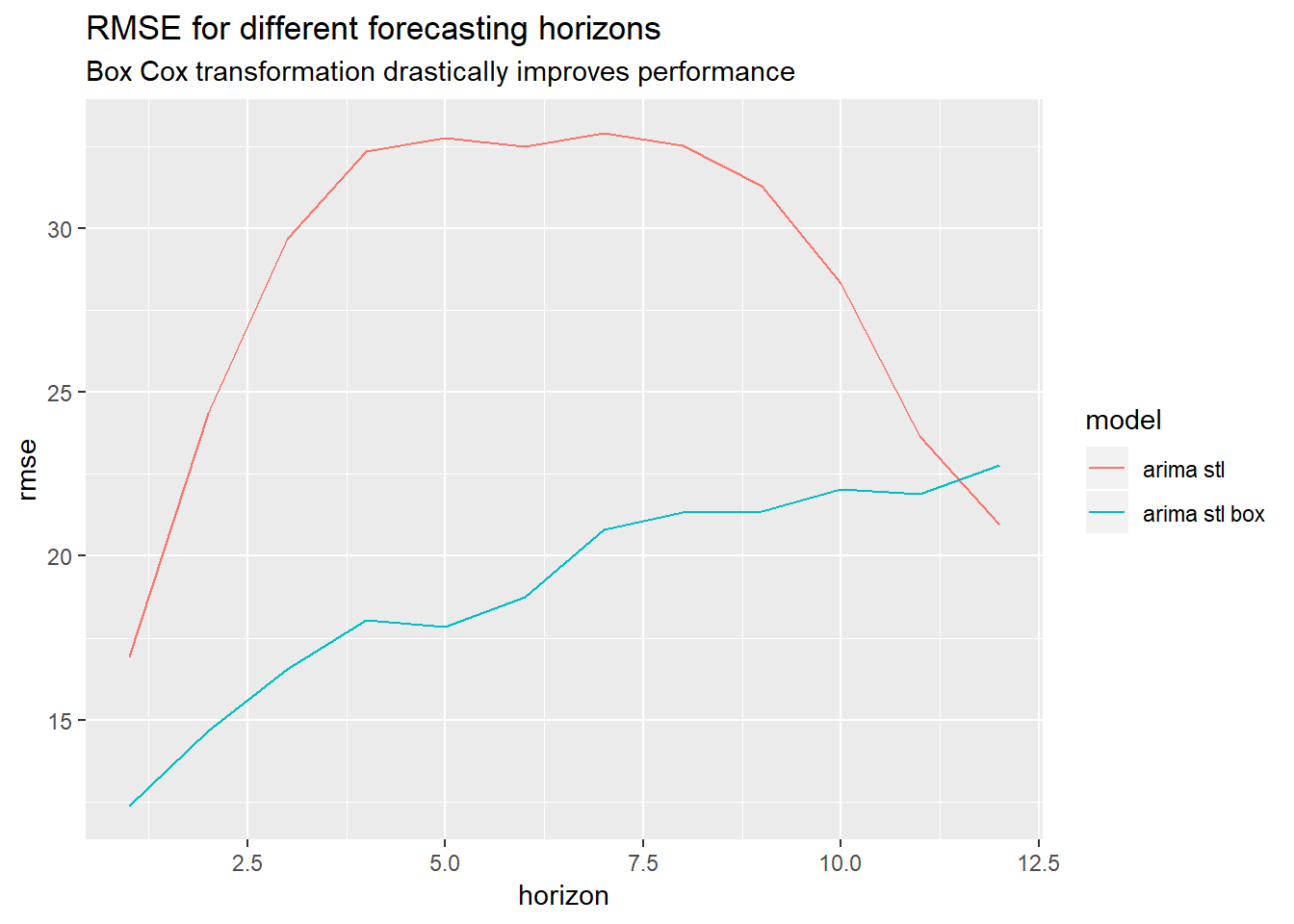

For a final test, let’s add a STL decomposition to our models and see how it affects performance with(out) Box Cox transformation.

STL decomposition in combination with Box Cox transformation

We are now running the same experiment again, but this time we are going to:

- Apply a STL decomposition,

- forecast the deseasonalised series after a Box Cox transformation and

- backtransform and re-seasonalise the data

Again, applying a Box Cox transformation helps a lot for most forecasting horizons.

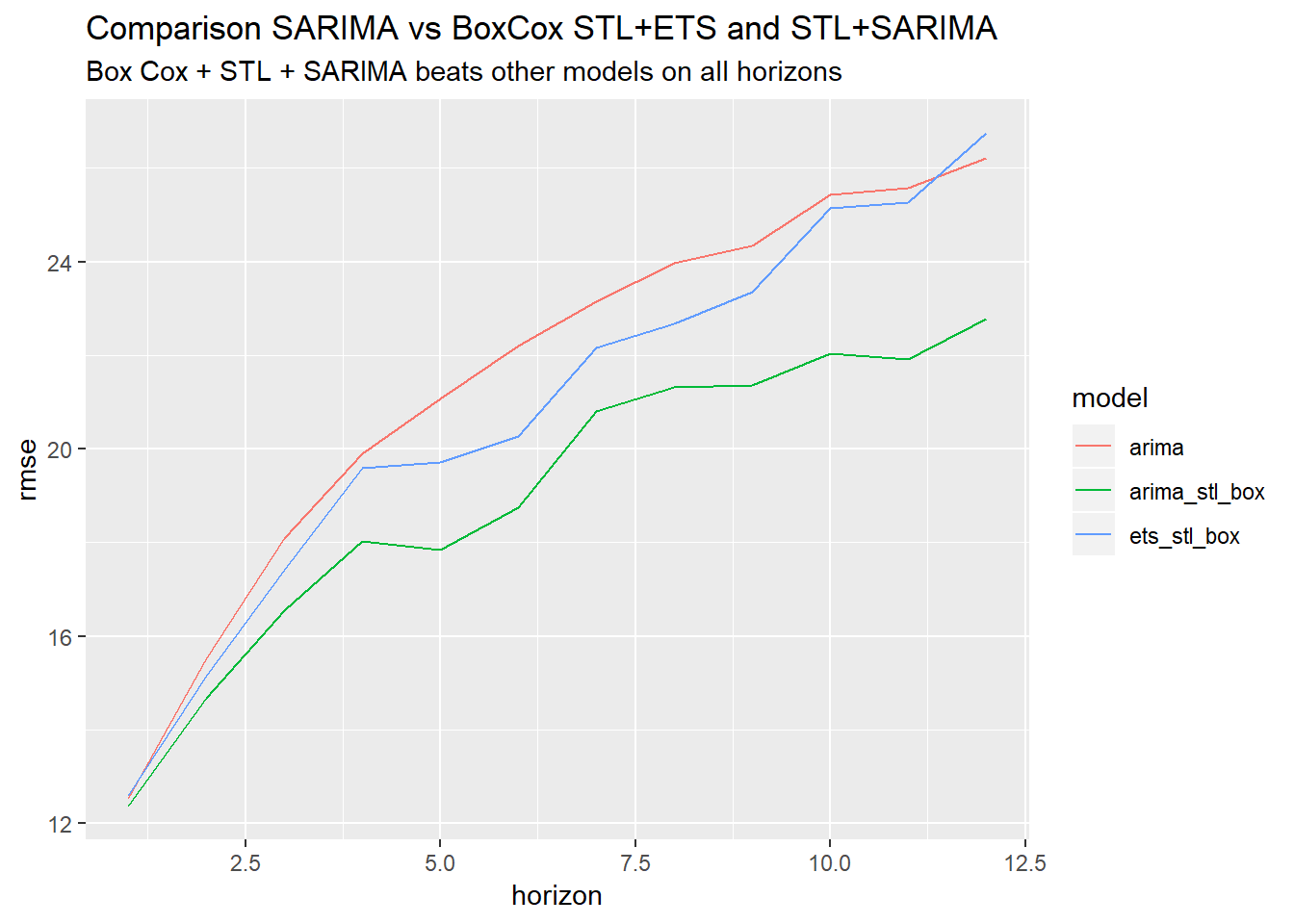

How do the STL with Box Cox perform compared to the plain-vanilla sARIMA model?

rmse_best_arima_ets = data.frame(rbind(rmse_arima, rmse_arima_stl_box, rmse_ets_stl_box))

rmse_best_arima_ets %>%

cbind(model = c("arima", "arima_stl_box","ets_stl_box"), .) %>%

tidyr::gather(key = "h", value = "rmse", 2:13) %>%

dplyr::mutate(horizon = rep(1:12, each = 3)) %>%

ggplot(., aes(x = horizon, y = rmse, color = model)) +

geom_line() +

ggtitle("Comparison SARIMA vs BoxCox STL+ETS and STL+SARIMA",

"Box Cox + STL + SARIMA beats other models on all horizons")

We can see that the combination BoxCox+STL+SARIMA outperforms all other models.

So what is our conclusion? Should we apply a Box Cox transformation or not?

Conclusion

We saw that in certain cases applying a Box Cox transformation can drastically improve performance while in others it decreased performance a bit. The Box Cox transformation really shined in combination with STL.

So to sum up: Box Cox transformations can help with forecasting and should be in every practitioners toolbelt, but with any technique, there is no free-lunch so check your data. As always the answer is: it depends, but based on the experiments it does not seem to hurt much (at least in this case:)

References

Rob Hyndman’s excellent book:

- Forecasting: Principles & Practices, Second Edition

The derivation of the Box Cox Bias correction is based on:

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Taylor_expansions_for_the_moments_of_functions_of_random_variables

- https://robjhyndman.com/hyndsight/backtransforming

You can find an analytic derivation based on log-normal r.v. here:

There is also an interesting section about using transformations to restrict forecasting ranges: