One of the things I particularly like about working in data science, is the science part: Figuring out the right questions to ask, how to frame a problem correctly and finally trying to solve it.

While there are many problems that you can simply solve by library(caret) or from sklearn import * and dumping your data into an appropriate algorithm those are usually just low-hanging fruits and often not particularly interesting to work on either.

In this post, I want to show you the framework I developed (more correctly: which I am still developing) to help me solve interesting data science problems.

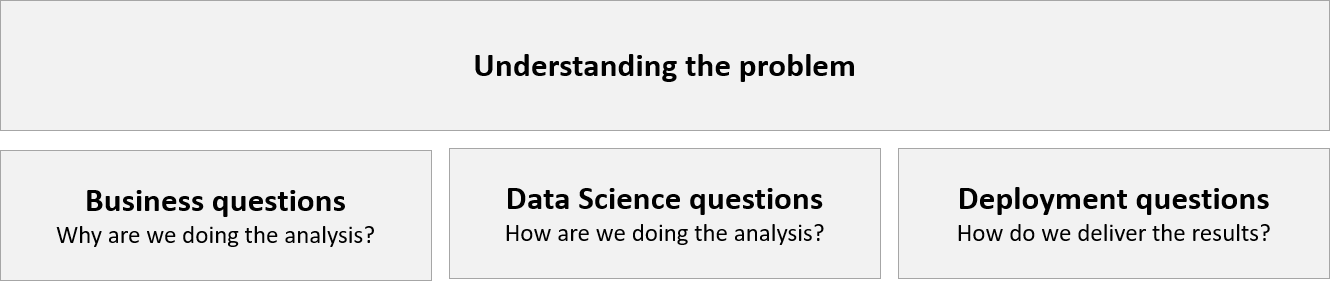

Understanding the problem

This sounds like a no-brainer, but I fear it is still often underappreciated just how important it is. Imagine for example you get the following request from a business unit at your company:

We need an accurate prediction of sales volume for sales territory XY.

Some pretty standard follow-up questions that immediately come to mind are:

- We have to define how we measure ‘accurary’. Should we use RMSE, MAE, MAPE or some custom metric?

- Do you want your forecast with daily data or are weekly/monthly totals sufficient?

- How much historic data do we have?

While those questions are all relevant they do not really help you in getting a better understanding for the problem in question, because they miss the most important point:

What is the goal of this analysis, i.e. what do you want to do with the information?

I like to divide the questions I ask into 3 categories:

Business questions help you understand the “why”. Why are we doing the analysis? How are our results going to be used?

At a minimum, I like to ask the following questions:

- What is the goal of the analysis?

- How much time do we have to work on the problem?

- When is a solution good enough?

Without a clear understanding of the goal of your analysis you cannot suggest alternative solution strategies and you cannot check whether your loss function and your accuracy measure are appropriate.

Imagine that the goal of doing the sales volume forecast is to plan the number of delivery trucks. Each truck has a capacity of 500 goods and you need a minimum of one truck anyway. So as long as your model helps to accurately determine when you need an additional truck or when you can make do without, it is doing its job even if the forecast is off by say 50 goods on average.

This directly ties in with the question: “When is a solution good enough?”. As a rule of thumb, if you cannot act on the additional accuracy your forecast provides, it is probably advisable to stick to a simpler solution. If you only need to forecasts on a monthly level, forecasting on a daily level to produce monthly forecasts is likely going to introduce additional complexity that will likely not substantially change your results, but makes it harder to find a solution quickly.

I then go on to ask ‘classic’ data science questions that I already stated in the beginning:

- How do we measure accuracy?

- What loss function do we use, i.e. what is the metric we optimize?

- What is the desired level of granularity across all relevant dimensions? (e.g. daily vs. monthly, item level vs. category level, address level vs. zip code level)

- What kind of data is available?

- How much historic information do we have?

- Has someone already tried to answer this or a similar question in the past?

As I already mentioned, we need a thorough understanding of the problem in order come up with an appropriate measure of accuracy and a loss function that is suitable for our problem.

The last question is particularly important for a couple of reasons:

- If someone tried to solve this or a similar problem in the past we can use this solution as a benchmark.

- Furthermore, we can incorporate the previous solution into our own framework and potentially avoid re-inventing the wheel.

- We can learn from errors that were made in the past and hopefully avoid falling into similar traps.

- Finally, we can use the previous solution to get a feeling for the difficulty of the problem, which is important when we need to estimate how much budget we are likely going to need.

Finally, I go on to discuss deployment questions:

- Is this an ad hoc analysis that is only done once or should it be automated in the future?

- How often do you need an updated forecast?

- When do you need an updated forecast?

Depending on whether this is a one-off or a repeated analysis, we can invest less or more time in building re-usable parts and writing unit tests and so forth.

Forgetting to ask the last question actually nearly tripped me up once. I had to provide a day-ahead forecast every day by around 3 o’clock in the afternoon. Trouble was that the data for my most relevant features was not yet available in the database by that time. So I had to make do with data from the day before.

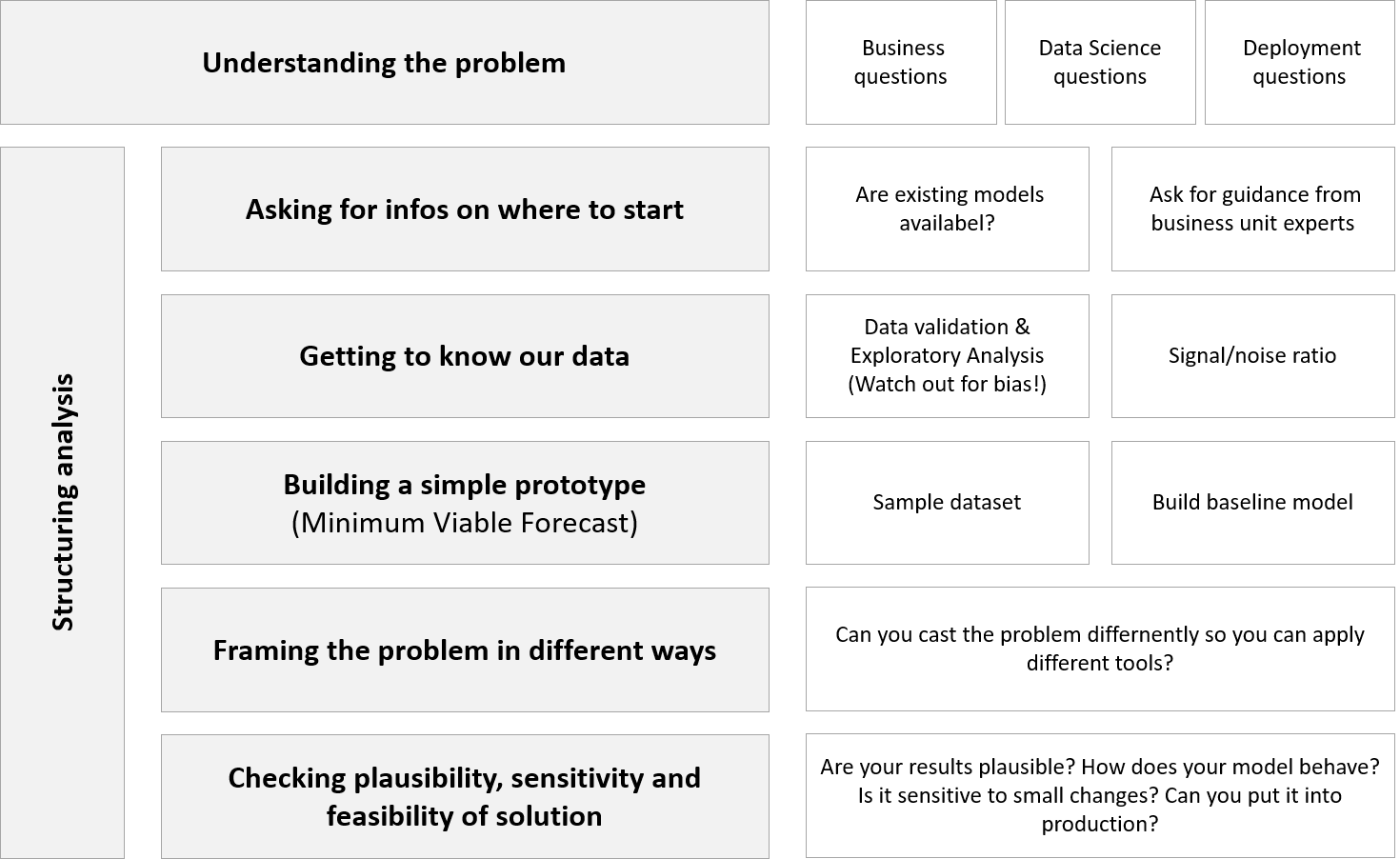

Structuring your analysis

Before I dive into the analysis I like to draw up a structure. Doing that helps in two important ways:

- It helps my team and myself to work in a systematic way that allows us to track work items and divide work efficiently.

- It helps communicate our progress to our clients.

We usually follow a template like this:

I will explain each point in more detail in the next sections:

Asking for infos on where to start

In many cases, when a business unit asks you to solve a problem for them they have already invested time trying to solve the problem themselves and ask for help because solving the problem proved more difficult and/or resource intensive than initially anticipated. In some cases, somebody already tried to solve the problem in the past and there might already be a working prototype or something similar that you can build on.

So there is a good chance that you do not need to start from scratch and can build on the experience of your colleagues. Even if there is nothing you can build on directly, your colleagues in the individual business units usually have lots of experience and can help you decide where you should focus your attention and help you check whether your results are plausible.

Getting to know our data

A large part of data science is understanding and cleaning your data and for a very good reason:

- At first, we need to check if the data available is actually sufficient to answer our questions.

- Then we have to make sure data quality is high enough and

- we have to check our data for bias that might lead us astray.

- Finally, we need to make sure we actually understand what data we are working with.

Data quality is especially problematic if we use algorithms with high variance that are easily tripped by a high level of noise in our data.

However, I would argue that not really knowing what the data you are working with means is actually much more wide spread than one would believe and more problematic. You are bound to stumble over columns in a database with names that either seem to be pretty clear, but in reality mean something completely different or names that are just plain confusing.

For this reason I suggest you always try to follow these steps:

- Ask the data owner to provide you with descriptions for all individual fields including allowed data ranges.

- Then go to somebody who actually works with the data on a daily basis and ask them for their input. Ideally, the two descriptions match, but likely they won’t.

- If they don’t try to bring both parties together and try to clarify the issues.

- Do logical validation of your data based on the data ranges provided by the data owner and common sense.

- For any problems that you find, prepare a short summary with example data for discussion.

- Repeat until you are satisfied with data quality.

Data validation & exploration

I suggest you always start by calculating summary statistics for each column in your dataset. The R function skimr::skim() offers very nice high level summaries for different data types. At a minimum you need to check:

- Number of missing values

- Quantiles, minimum and maximum for numeric variables

- Number of unique values for categorical/nominal variables

You can define validation rules using the package validate.

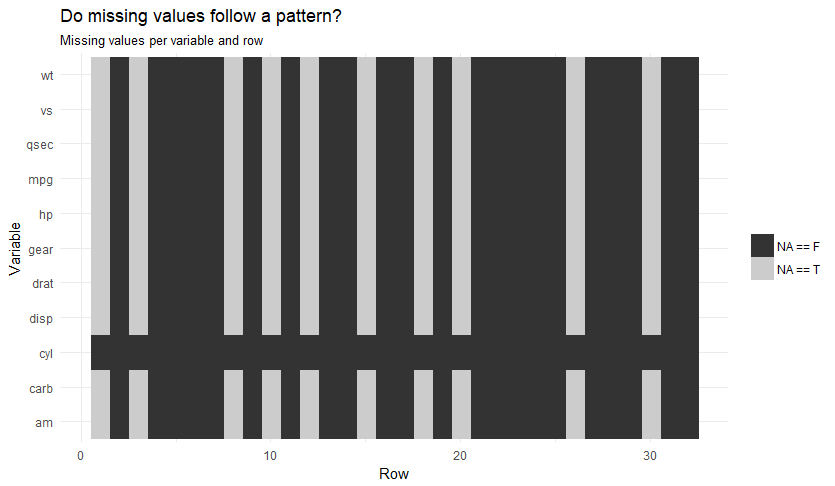

Missing value analysis is a whole topic in its own right, but I suggest at a minimum you try to plot a missing value map to quickly check if values are missing in a systematic way:

It is also good practice to show how many rows you remove with each data cleaning step and to save all removed rows in a separate dataset for further analysis. In many cases, missing or wrong information is caused by some underlying problem and therefore non-random.

Before you begin with your exploratory analysis, you need to split your data into a train/validation and an independent(!) test set in order to avoid introducing bias. This is especially relevant for time-series data.

Imagine the following scenario: You are asked to do a sales forecast for 3 different territories and you start by doing some exploratory analysis on the aggregated data from all three territories. You see that sales increased exponentially in the last year and you decide to build a model to account for this phenomenon. You then do some cross-validation and get a very good fit on both train/validation and test datasets. You fell victim to foresight bias: you introduced information into your model that was not available at the point in time where you trained your model, in essence you were looking into the future.

Signal/Noise ratio

Signal refers to an actual deterministic pattern that drives the process of interest. Noise represents all the random shocks that obfuscate the true signal such as:

- incorrect data (which might not be random) and

- random shocks such as a problem at a construction site that causes a traffic jam

A strong and clear signal means ceteris paribus that our work as data scientists is easier. The more noise there is and the weaker the signal, the harder it is to find a model with high predictive power that generalises well.

Using my train/validation set I usually plot the distribution of my target variable along a couple of dimensions (e.g. sales volume distribution by day of week) to get an idea of the variability of my data. With time-series I also like to look at the distribution of changes week-over-week or month-over-month and at the autocorrelation structure. Ceteris paribus, higher variance in the target variable and low autocorrelation means a tougher problem for you to solve. In a clustering context I look at the distribution of the classes along a couple of dimensions and pay attention to class balance.

Building a simple prototype (minimum viable forecast)

Working with an easy sample

In the beginning I like to start with a simple example. While we could start with the entire dataset this makes it harder to pin down the source of a problem:

- Is the technique we use not appropriate for the problem?

- Is there an error in our code?

- Is the dataset to large to fit into memory while processing?

- Is the data still fishy?

- Are there any corner cases we have not though of?

Plus, working with a sample means we can iterate more quickly.

A quick and dirty baseline

Next, I always try to establish a baseline that I use to compare my models against. Some problems are inherently harder/easier than others so you need a benchmark to compare against. If somebody already build a model in the past, I like to use it as a baseline since my model needs to beat the old benchmark otherwise it is not worth the effort to implement it in many cases.

A few ways to generate baselines are:

Time series baselines

- Martingale baseline: tomorrow equals yesterday or last Monday equals next Monday, etc.

- Simple regression model using available data

- Moving-average/Moving-median

Clustering baselines

- Always predict majority class

- k-means clustering using available data

Framing the problem in different ways

My colleagues and I recently worked on an interesting problem where we had to predict the most likely 1h-arrival time window for each stop point on a given tour. We decided to tackle the problem the following way:

- Try ‘standard’ machine learning approaches like gradient boosting first and check if the accuracy is sufficient.

- If not, try to model the spatio-temporal relationship in the data more explicitly.

Intuitively, the number of stop points and the stops themselves should play an important role in determining the most likely 1h-arrival time window. So we build features to capture the historic arrival times at a given stop point and the absolute order the stop had in a given tour (say stop #34) as well as its relative order (e.g. first half of the tour). We ran everything through a gbm algorithm and not surprisingly, the most important features where absolute order, relative order and information about historic arrival times.

This got me thinking: Maybe we should not try to forecast the arrival time directly, but instead forecast the order of the stops for a given tour. I asked my colleagues to re-run our gbm with two additional features: the actual order of a stop point and the relative order of a stop point for a given tour. As it turned out, those two features helped improve our accuracy by almost 50%. So if we can predict the ordering of stop points, we can determine the 1h-arrival window pretty easily.

So in essence, we reframed our problem from:

Find the 1h-arrival time given some explanatory variables X

to

Find the most likely ordering of stop points given some variables X and use this information to forecast the 1h-arrival time

In many cases, reframing the problem can actually simplify your analysis a lot.

AllMany roads lead to Rome (but some are considerably shorter and easier)

So if you are stuck, try to check if it is possible to recast/reframe your problem.

Checking plausibility, sensitivity & feasibility of solution

Checking plausibility is particularly important if you use black box algorithms to understand how your model behaves in extreme cases.

Let’s look at an example: Suppose again, you are asked to forecast volume of some goods. Obviously, volume needs to be greater or equal to zero. However, it is also a good idea to check how fast volume varies over time. If the maximum 1 week change in volume in the past was 50% and your model forecasts 300% you might want to check why you got this output. You should probably also check how your model behaves around Christmas and New Year. In many countries you would expect volume to level off after Christmas for instance.

It is also advisable to check how sensitive your model reacts to changes in your input data. In many real world scenarios it is preferable to have a slightly less accurate, but more robust model.

It’s a good idea to include some ‘unit tests’ to catch strange results early.

Finally, you should always keep in mind that your solution may need to scale later. I stumbled over this particular issue once. I built a fairly good, but way to resource intensive model that I could not scale quickly enough with the hardware I had available at the time. So I ended up restricting the training time of the model, which resulted in less than optimal performance and still posed quite a few problems infrastructure wise. In hindsight, I should have probably stuck to a simple model in the beginning and gradually switched to a more resource hungry version later on.