I am a long time R user and I like R a lot. Coding in RStudio is a breeze and most every problem already has an associated package with a solution on CRAN. Nevertheless, I wanted to learn Python as well, because I firmly believe, if you only have a hammer, then every problem looks like a nail. Setting up a Python development workflow for data science proved to be a bit more work than I originally anticipated and that is why I wanted to provide a quick start guide for experienced R developers who want to get up to speed in Python.

First I will dive into setting up your coding environment on Windows 10 (macOS and Linux have similar, easier setups, but at work our laptops are Windows only, so here we go …). Then I will quickly cover how to work with virtual environments, install packages, write your own Python package with unit tests, documentation, linting and how to debug your code. Since I like working with Docker a lot, I will also include some additional information on making your Python code work nicely with Docker.

Getting started - VS Code as Python IDE

There are lots of great Python development environments out there, but personally I am very much in love with Visual Studio Code. I like a lightweight editor that I can customize to my hearts content. Plus, VS Code is available for Windows, macOS and Linux and is completely free to use. So this post will focus on VS Code.

Prerequisites

Before we begin, you need to:

- Download and install Visual Studio Code

- Download and install Anaconda Python 3.6

- Install Microsoft’s Python extension

Feel free to choose a different Python distribution, but I would recommend using Anaconda Python on Windows. Anaconda comes with most of the packages you are going to need for scientific computing and you do not need to build packages from source (which can be a pain on Windows).

After you completed the steps above, create a file called hello_world.py with the following code:

print("hello world")

Press ctrl+shift+p and type Python: Run Python file in Terminal and press Enter. You should now see ‘hello world’ printed to the integrated terminal.

Working with virtual environments and installing packages

When you work on multiple projects sooner or later you will run into dependency issues:

Project A needs library XY version 1.1, but Project B needs library XY version 1.2 and there are lots of breaking changes between package versions. How can we fix this situation?

One way to resolve this kind of problem is to isolate project dependencies using virtual environments. A virtual environment specifies and isolates the Python interpreter you want to use for a given project and (depending on which virtual environment tool you use) most/all dependencies. As already mentioned before, we will focus on Continuum Analytics’ package and dependency management system conda that is part of Anaconda Python.

conda provides a couple of very nice benefits compared to other similar tools:

- It works on Windows, macOS and Linux

- While it was originally developed for Python, you can also use it for other languages such as R

condaallows you to install and update packages easily and works withpip install(the Python equivalent to R’sinstall.packages())

Note: If you use Anaconda Python, do not change the default terminal in VS Code to PowerShell. Anaconda cannot active environments properly using Powershell.

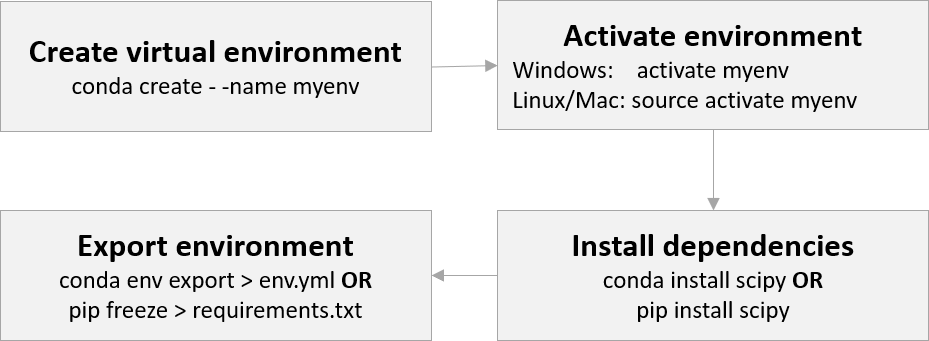

Before we start, here is a high-level overview of how to use virtual environments:

Let’s start by creating a virtual environment called myenv:

Creating environments & installing packages

Open an integrated terminal in VS Code and type

# create the environment

conda create --name myenv

# Active/deactivate the environment

activate myenv

deactivate myenv

# create environment with specific Python & package versions

conda create -n myenv python=x.y

conda install -n myenv pip scipy=a.b.c numpy matplotlib

Note: You have to use source activate myenv on macOS/Linux.

It is also possible to use pip to install packages in a conda environment:

# first install pip using conda

conda install pip -y

# then use pip to install scipy

pip install scipy

You can select an existing environment by pressing ctrl+shift+p and typing ‘Python: Select Interpreter’ or clicking on the interpreter icon currently active on the right side of VS Code’s menu bar at the bottom.

You can also specify a default package list that is installed every time you create a new environment. Furthermore, it is possible to clone existing environments using:

conda create --name myclone --clone myenv

Information about environments

Use

conda info --envs

to get a list of all environments available.

You can easily see which environment is currently active by looking at your terminal.

(myenv) C:\your-working-directory

The active environment is shown in (). Alternatively, you can see an asterisk * in front of the active environment if you use conda info --envs.

To see which packages are currently installed in an environment run:

# to get a list of all packages

conda list -n myenv

# to check for a specific package (returns nothing or package version)

conda list -n myenv pip

Exporting an environment

An environment can be exported using:

# writes a conda config to your current working directory

# that can handle both pip and conda packages

conda env export > file_name.yml

# Build environment based on file_name.yml:

# to create an environment from scratch

conda env create -f file_name.yml

# to build an environment based on a .yml config run in an existing environment

conda env update --file file_name.yml

Deleting an environment

If you want to delete an environment and all associated content run:

conda remove --name myenv --all

Note: Don’t forget, if you use a Linux based Docker image you have to run source activate myenv!

You can also use conda to save environment variables.

More detailed information is available on the conda help pages.

Conda environments in Docker

Creating Docker containers with pip install is super easy. All you need to do is specify a ‘requirements.txt’ file for pip to use in your Dockerfile:

COPY requirements.txt ./requirements.txt

RUN pip install -r requirements.txt

However, conda always creates a virtual environment if you want to restore an ‘environment.yml’ file. So you have three options:

- Use

conda installin your Dockerfile and specify all dependencies there - Use

pip freeze > requirements.txtif everything can be installed usingpip - Use conda inside your Docker container to setup a virtual environment in which to install the packages specified in your ‘environment.yml’ and either do:

Option 3.1 which I found on Docker and conda (shortened and modified):

FROM continuumio/miniconda3:latest

WORKDIR /app

COPY . /app/

COPY environment.yml /app/environment.yml

## create conda environment from environment.yml

RUN conda env create -n myapp -f environment.yml

## activate the myapp environment

ENV PATH /opt/conda/envs/myapp/bin:$PATH

Alternatively, you can try:

Option 3.2 from Using Docker with Conda Environments a bit shortened and modified:

FROM continuumio/miniconda3:latest

WORKDIR /app

COPY . /app/

COPY environment.yml /app/environment.yml

## Using bash! conda does NOT support sh, which is the Docker default (/bin/sh)!

ENTRYPOINT [ “/bin/bash”, “-c” ]

CMD [ “source activate your-environment && exec python application.py” ]

From module to package

Coming from an R background, I was a bit confused at first: People were sometimes talking about Python modules and at other times about Python packages. I was never quite sure if the two are merely synonyms or actually different concepts and if so, how they are different and how they relate to R’s concept of source files and packages.

Python module

Turns out, Python modules are basically equivalent to plain R files, but they get imported into their own isolated namespace. So in essence, a module is sort of an ‘R-package-light’.

Comparison: R file - Python module

| R | Python | |

|---|---|---|

| Code source | file.R | file.py |

| Name | source file | module |

| Import command | source(file.R) | import file |

| Scope | Global Environment (default) | module environment |

Every .py file can be used as a module, although some naming restrictions apply (e.g. don’t use a dot (.) or a question mark (?) in the filename, because they interfere with how Python searches for modules).

There are a couple of ways you can emulate this behavior in R. You can source(), i.e. import, files into their own environment or use packages such as modules or import. Still, I really like that in Python this is the default behavior to import additional code.

Module search path

When you use import to load a Python file as a module, Python will start looking in the directory of the caller (i.e. where your Python process was started) and then will recursively work its way up through the Python search path.

To take a look at the current search path run:

import sys

sys.path

When you use conda, it modifies this search path for you.

Package search paths in R work more or less the same way. R always starts by looking for a Rprofile.site file located in the R install directory. Afterwards, it will search for .Rprofile files in the directory of the caller and if it does not find one, in the user’s home directory and runs it. If either Rprofile.site or .Rprofile modify the search path, the new search path is used. Otherwise, R defaults to the user library and then to the system library.

To take a look at R’s current search path or to modify it run:

# print current search path to console:

.libPaths()

# modify search path for current session:

.libPaths = .libPaths(c("some/path/here", .libPaths()))

Or automatically alter your search path on R startup by putting the following in your Rprofile:

.First = function() {

print("loading .Rprofile")

## Append custom library folder to libPath

.libPaths(c("/usr/r_libs", .libPaths()))

}

Note: If you use RStudio’s build tools, you have to place your .Rprofile in the directory containing your RStudio project.

Python package

R enforces a pretty strict structure on any package. Python on the other hand considers any directory containing an __init__.py file a Python package.

Suppose you have a folder called foo that contains __init__.py, bar.py and some_other_module.py. Module bar.py contains a function print_bar():

foo/

__init__.py

bar.py

print_bar()

some_other_module.py

You can import module bar from package foo using:

## importing using full name

import foo.bar

# or

from foo import bar

## specify a shorter namespace

import foo.bar as fb

# or

from foo import bar as fb

## import everything into global namespace

from foo import *

Python will search for your package and execute __init__.py. Afterwards, it will search for bar and import it into the foo.bar namespace.

Comparison: R package - Python package

| R | Python | |

|---|---|---|

| Name | package | package |

| Structure | R script + man folder, DESCRIPTION and NAMESPACE files | multiple .py files in a folder with __init__.py file in project root |

| Import command | library(package) or package::function() |

import package / import package as pkg |

| Scope | package environment | package environment |

Exporting/importing in Python

If you have developed an R package before, you will remember that a user can always access all objects using :::, but you can specify which objects you want to be available to the user by exporting them, so the user can access them by calling library() or ::.

In Python you can specify which modules/objects of your package to export in your __init__.py:

__init__.py:

# 1

## expose modules for: from foo import *

__all__ = ["bar", "some_other_module"]

#2

## expose modules for users:

from foo import bar

#3

## expose objects for users:

from foo.bar import print_bar

# or shorter:

from .bar import print_bar

Let’s take a closer look at those three import options in __init__.py:

__all__specifies which modules are available if the user runsfrom foo import *- Using this option, the user can write

foo.bar.print_bar()after runningimport foo. - Now the user can access our function using

foo.print_bar()

While you can import all objects of a Python package into the global namespace using from package import * (the equivalent of library(package) in R) this is considered bad practice and the following methods are preferable:

import package as pkgorimport packagefrom package import specific-object-1, specific-object-2

I really like that you can shorten package names using import as in Python. The default way in R to achieve this functionality is to use package::function, which can be quite verbose (although you can do function <- package::function or use e.g. the import package).

Reloading modules/packages

If you changed parts of your package and you want to see the changes in your Python console you can either start a new Python session and import your package again or reload it. Reloading modules and packages works differently depending on your Python version. From Python 3.4+ you can use:

from importlib import reload

import foo.bar as fb

<some code here>

## Now you made some changes to the package foo.bar and want to reload it

reload(fb)

This is equivalent to using devtools::load_all() or building and installing the package again in R.

Documenting your project

‘The Hitchhiker’s Guide to Python’ recommends to always include the following files in your project’s root directory:

- A

README.rstfile giving an overview of important information for users/maintainers like setup instructions, general infos about your code and aTODOsection - A

CHANGELOGto show changes in your code from version to version - A

LICENSEfile

In R I use Roxygen, which is based on Doxygen, to document my code. While you can use Doxygen for Python, the recommended tool by the Hitchhiker’s Guide is Sphinx. Sphinx can convert reStructured text markup to HTML, LaTex and other formats (so it is equivalent to Pandoc in a way). Sphinx docs can be hosted for free on Read The Docs and rebuilding your documentation can be triggered automatically every time you commit to your repository.

In Python you use docstrings to document functions, modules and classes:

# leading comment block = programmer's note

def print_bar(string1: str, string2: str) -> str:

"""

print 2 strings to console

This function uses PEP 484 type annotations and

prints two strings to the console.

Args:

string1: some text to print

string2: some more text to print

Returns:

Prints string1 and string2 to the console

>>> print_bar(1,2)

'1 2'

"""

return print(string1, string2)

Using tools such as Doctest allow you to embed unit tests in your docstring (prefixed with “>>>”, see above).

Docstrings can be accessed by using the help() function.

I hope you found this little guide useful:)